Cardiac structure#

This section goes through some terminology which might be useful for understanding the remaning chapters. Our model takes into account the explicit geometrical representation of cells (cardiomyocytes) embedded in an extracellular matrix (ECM).

Cardiac anisotropy#

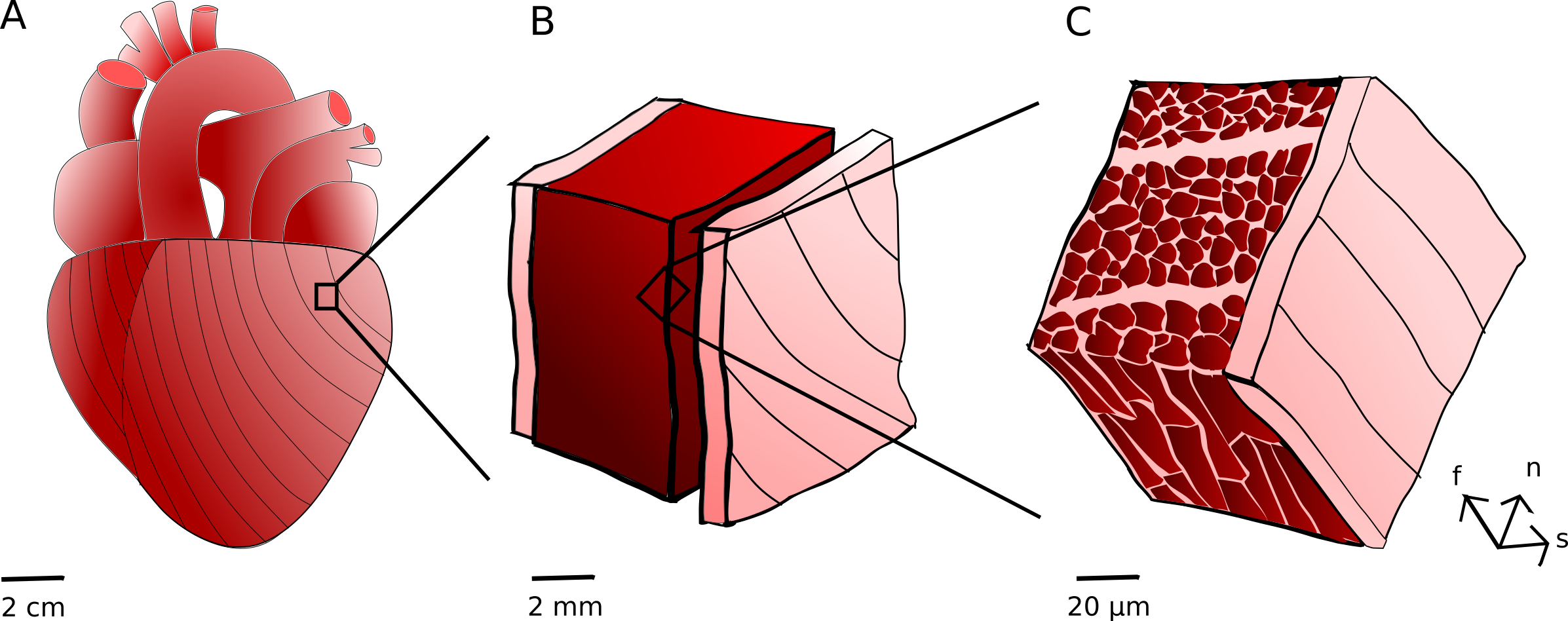

Myocardial structure at different scales. The tissue in the heart (A) can be considered as composed by several layers (B). The myocardium is enclosed by an inner endocardium layer and an outer epicardium layer, of which the latter is also considered a part of the larger pericardium layer. The myocardium © is, in volume, mostly composed of cardiomyocytes (cardiac muscle cells). These are surrounded by the endomysium (closest to the cells), the perimysium, and the epimysium, all different extracellular matrix components. These structures gives rise to a local fiber direction \(\mathbf{f}\), a sheet direction \(\mathbf{s}\) and a normal direction \(\mathbf{n}\). The global fiber direction distribution, as distributed close to the epicardium, is indicated by streamlines in (A).

The cardiomyocytes are locally aligned in their longitudinal direction, defining what is called the fiber direction \(\mathbf{f}\). Considering the whole heart as observed from the outside, these follow a helix pattern. The cardiomyocytes are further believed to be organized in laminar sheets, separated by perimysium layers, which motivates a second axis for local alignment, the sheet direction \(\mathbf{s}\). Finally, one commonly defines the normal direction \(\mathbf{n}\) to be aligned with a third axis, which is given by the cross product between the unit vectors that define the fiber and sheet directions.

Geometries and cardiac structure#

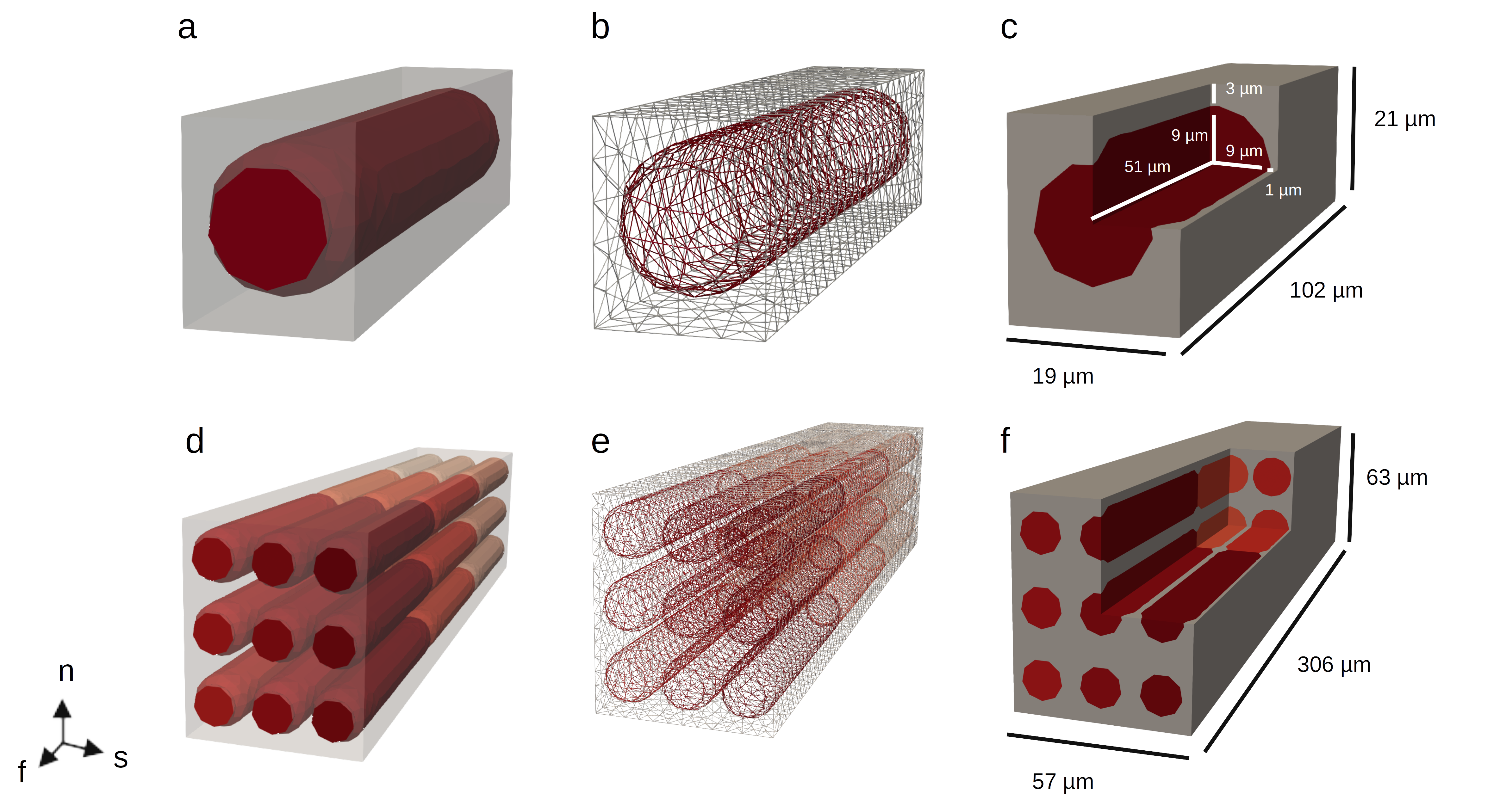

Geometries and meshes. The code in this repo is developed for geometries / meshes like these. (A-C) Single cell; geometries, mesh structure, and dimensions. (D-F) Tiled mesh \(3 \times 3 \times 3\) cells.

The geometries we work on represent the cellular structure on a local level, in a very idealized way. In principle, the geometrical domains can be way more complicated. However, keeping them simpler make it easier to generalize from one cell to multicellular domains.

We have a distinct cellular longitudinal direction, which we will take to be the fiber direction \(\mathbf{f}\). For practical purposes, in the geometries we have generated, this is aligned with the \(\mathbf{x}\) direction in a Cartesian coordinate system. Next, as visible in subfigures C and F in the figure above, the cubical structure representing one unit is slightly thicker in one direction than the other. This is meant to resemble layers of perimysium. Ideally, we should have a geometry with a few cells before adding a layer; but for simplicity we assume that the layers are one cell thick. We take the sheet direction to be in the direction where the ECM layer is thin (aligned with the \(\mathbf{y}\) direction) and the fiber direction to be in the direction where the ECM layer is thicker (aligned with the \(\mathbf{z}\) direction).